Repost of author’s article as seen in Chief Executive Magazine | January 28, 2016

by William J Holstein

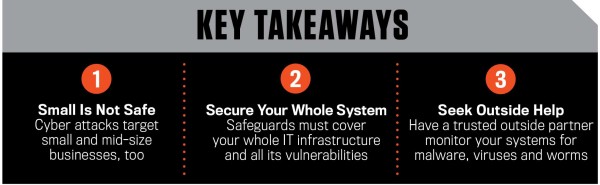

Attacks on large companies make headlines, but smaller companies, too, suffer cyberattacks. Here’s how to protect your business.

Chuck Provini knows he has a bright red bulls-eye painted on his back. As CEO of startup Natcore Technology, he hopes to develop technologies that will render the use of silicon crystals to make solar energy panels obsolete. Provini’s Rochester, New York-based company, which works with U.S. Department of Energy research labs, among others, to develop new technologies, represents a threat to China’s solar energy industry.

China’s position in solar energy is based on silicon, and the Chinese are targeting solar energy as a strategic industry of the future. The Chinese show no hesitation in trying to crack open the IT systems of American companies and government agencies to obtain proprietary information—despite President Xi Jinping’s promises to the contrary.

“Try to create several boxes that people cannot access and keep as many things away from the Internet as possible.”

“Small companies do not typically have the budget to build all the great and wonderful things that bigger companies do, and they still get hacked,” says Provini, who dealt with top-secret issues while serving in the U.S. military. “So you try to create several boxes that people cannot access and keep as many things away from the Internet as possible.”

One of his large shareholders in the cyber intelligence business was the first to recommend that Provini keep his secrets in different modules not connected to the Internet. “That’s what you learn—to keep modules that are independent and accessible only on a need-to-know basis. Sometimes the simplest mechanisms are best.”

Not everyone can follow Provini’s example. In fact, the vast majority of small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) don’t have that option. Trends in the business world demand that smaller companies establish computerized supply chain connections with their larger customers and more connectivity, rather than less. This connectivity, in turn, creates vulnerability.

DOORS WIDE OPEN

The hackers who breached Home Depot and Target won entry through suppliers. It is precisely because of their connections with larger companies that SMB companies get targeted.

“A lot of smaller company CEOs are saying, ‘It won’t happen to me,’” says Devon Nevius, executive vice president of Upward Technology in Portland, Oregon, which provides Internet security for about 50 small companies in that region. “They’re saying, ‘It’s more of a Home Depot thing.’ But that is naïve.”

Cloud computing, or the use of large company server farms to store data and use software on demand, is a hotly debated piece of the emerging debate about cybersecurity at SMBs. Some smaller company CEOs believe that basing crucial information in systems managed by Amazon Web Services, IBM or Microsoft makes their data and intellectual property safer because the big IT providers boast the latest technologies and the best brainpower. Others argue that the systems those big companies use to store the data of thousands of companies makes them an increasingly

attractive target for cyber villains and that it is only a question of time before they get hacked.

Many smaller companies use a hybrid form of cloud computing, meaning that some data and some functions are based in the cloud while others are located on-premises. Trying to understand the security implications of hybrid systems can be difficult as well.

Other technological trends also open doors for the bad guys. Many SMB CEOs haven’t realized that doing something as simple as outsourcing a call center creates an opening because of the application program interface (API) used to link the call center company and the customer. It can be attacked and employed as an entry point into all the company’s systems. Elsewhere, the trend called the Internet of Things (IoT)—the massive linking of sensors, cameras and computers—promises big productivity gains but will only intensify the security challenge.

PROTECT AND SECURE

Interviews with computer security experts and consultants across the country—many of them young and brash but nonetheless well-informed—suggest that outside of a few regulated industries, such as banking and insurance, the majority of SMB CEOs have not taken sufficient steps to protect themselves. Hackers pursuing technical secrets may target startup companies in fields such as solar energy, genomics, pharmaceuticals, nanotechnology and other fields where American companies hold global advantage. More established companies that sell highly specialized equipment to aerospace and defense industries are also targeted.

Hackers don’t necessarily infiltrate smaller technology companies for what they have today—they may be more interested in what they can access once a smaller business establishes an alliance with a large company or is acquired. The cyber thieves can insert viruses and malware that lie dormant in a system until they are activated, which may be years later.

“IT departments are way behind.”

The attacking software can even work its way up through different levels of approval within a company’s system until it is accepted as legitimate. Other types of hackers seek information that can be sold on the “dark” Internet, the part that ordinary folks never see, and they go after the personal data of people who do business with hospitals, law firms or retailers.

The dark Internet is where hackers exchange code and brag about their exploits. The worst sort of hackers, however, are company insiders who have a beef with top management. They have security clearances—and axes to grind.

Most companies with less than $1 billion in sales a year cannot afford full-fledged IT departments with a dedicated chief security officer, and therefore may have only a handful of people managing a large, complex problem. Furthermore, when IT departments are aware that they have vulnerabilities and approach top management for funding to fix the problems, they are often denied that money. To compound matters, they fear that if they reveal too much about security gaps to their CEOs, they will be held responsible. “IT departments are way behind,” says Andrew Ostashen, co-founder of Boston-based Vulsec, another consultancy that specializes in smaller companies.

Most companies with less than $1 billion in sales a year cannot afford full-fledged IT departments with a dedicated chief security officer, and therefore may have only a handful of people managing a large, complex problem. Furthermore, when IT departments are aware that they have vulnerabilities and approach top management for funding to fix the problems, they are often denied that money. To compound matters, they fear that if they reveal too much about security gaps to their CEOs, they will be held responsible. “IT departments are way behind,” says Andrew Ostashen, co-founder of Boston-based Vulsec, another consultancy that specializes in smaller companies.

“They’re constantly climbing up the hill while the hackers are on top of the hill throwing rocks at them.” He notes that many SMBs have 10- and 12-year-old firewalls that cannot properly analyze the data flowing in and out of a company’s systems.

THE PEOPLE PROBLEM

One reality is that if the attackers can make direct contact with the people inside a company, they can almost certainly use employees’ social media postings to learn about their technological competencies and their personal interests. That helps them create special “come-on” messages, or phishes, that are so well-tailored that even a trained employee will click on an Internet link, introducing a virus or malware into the company’s systems. “The human is the weakest link,” says Ostashen, an “ethical hacker” who assaults companies’ systems to demonstrate their weaknesses. “If I can get to the human, I can almost always get in.” These types of attacks are also called remote social engineering attacks.

Another reality is that employees in all sizes of companies increasingly want to use their own smart phones or iPads to connect to their companies’ central nervous systems, whether from home or on the road. This creates another avenue the hackers can use if those communications are not encrypted. Employees who lose a company laptop loaded with sensitive information can create major problems.

Add it all up and it’s clear that CEOs of SMBs face a tremendous challenge in maintaining the vital flow of information and the creative exchanges among people inside their companies—and with business partners—without increasing the risk of getting hacked. And many are in denial about it, says Ostashen. “I go into a company and provide a roadmap for how to fix their problems, then go back six months later and find that the problems are actually worse,” he says. “Top management did not want to spend the money. They wanted to accept the risk.”

One executive who argues he and fellow CEOs of smaller companies are doing a solid job of protecting themselves is Ross Buchmueller of the PURE Group of Insurance Companies, based in White Plains, New York, a privately held firm with about $500 million a year in premiums (sales.) “The reality is that everybody is trying to harden their systems,” he says.

While he operates in a sector where regulators ask him about Internet security, he says it’s really his affluent customers he has to protect—or risk losing their business. ”We’re asking tens of thousands of wealthy families to allow us to manage their risks, which means protecting all the information they share with us,” Buchmueller explains. “We spend a lot of time worrying about how to do that.”

“The first rule of having great security is not telling everybody what you do.”

Buchmueller hired an expert to be in charge of his technology infrastructure, and the company’s core on-premises data center is managed with help from Oracle and IBM, using the latest encryption know-how. The company does use a cloud application from Salesforce.com that helps it manage relationships with customers, but he’s confident it is well-protected.

Reflecting the sensitivities of being a CEO who speaks publicly about his IT system, thereby possibly attracting unwanted attention, Buchmueller declined to identify a vendor that provides a software agent which sits on his company’s computers and servers looking for an intruder before that attacker can secure any data. “The first rule of having great security is not telling everybody what you do,” he says.

He also hires consultants to “stress” or attack PURE Group systems to find weaknesses. Then he meets with the ethical attackers—without his internal IT people in the room. “That way, we can get the kind of candor we need and know we aren’t kidding ourselves about how our internal team is doing,” he explains.

One decision that any CEO faces in seeking external help is whether to hire a neutral third party, such as PwC (the former PricewaterhouseCoopers) or a company that offers cybersecurity products and services. “We provide a level of objectivity because we do not have products to sell—some CEOs find that valuable,” says Quentin Orr, head of PwC’s cybersecurity practice, based in Philadelphia. “The perspective we’re offering is not tied to any one product.”

Often, says Orr, smaller companies have an IT executive who wears multiple hats and tries to do the best possible security job, but lacks the necessary training and resources. “We often find a sleepy IT staff that’s been in place for many years,” he says. “They have a mentality of just trying to keep the lights on.”

This can backfire in a big way. For example, after a small healthcare information company suffered a breach, it became clear the company had mishandled sensitive information belonging to its two largest customers, presumably hospitals or physician groups. The firm had a contractual obligation to notify the customers of the breach—and both terminated their relationships with the smaller firm, forcing it to declare bankruptcy.

“If you’re a small company handling the data of big companies, they are not going to cut you any slack,” Orr warns. “They want you to step up to their level.”

The advantage of dealing directly with a security firm as opposed to a neutral third-party is that it may possess deeper expertise. “It’s the difference between going to a medical generalist and a specialist,” says Joshua Goldfarb, chief technology officer of FireEye in Milpitas, California, which has emerged as one of the most visible Internet security firms. “If you have a cold or fever, you might go to a general practitioner. But if you need orthopedic surgery, you’re going to go to an orthopedic surgeon. We’re the surgeon. A new customer can tap into all the experience we have built up over a decade of experience as an organization.”

Last year, FireEye, which markets its own hardware and software, acquired a highly specialized computer forensics firm, Mandiant, that has been a leader in identifying and tracking government-sponsored or government-sanctioned hacking organizations, particularly from China.

It calls those organizations Advance Persistent Threats (APTs.) That acquisition enables FireEye to help its customers anticipate the “threat vectors” coming from other countries. Altogether, it has 3,700 customers in 67 countries.

“If an attacker wants to come after you, they will find a way in.”

FireEye’s core offering is what it calls a “virtual execution engine” complemented by dynamic threat intelligence to identify and block cyber-attacks in real time. “But if a company wants to partner with us, to operate in the world we live in, then we are happy to offer our solutions as a service,” Goldfarb adds.

Goldfarb offers CEOs two pieces of advice. The first is to adopt a balanced approach toward security, which is part prevention, part detection and part response. If a bad guy wants to get into your systems, the chances are that he can—no matter what prevention measures are in place. One reason is that traditional perimeter-based defenses are breaking down, partly because of more distributed computing systems and partly because of the proliferating use of handheld devices.

“If an attacker wants to come after you, they will find a way in and we need to mitigate the incident before the attacker is able to get the information he wants,” Goldfarb advises.

The second is to find a security partner who understands your business and takes a systematic approach to defending it, rather than merely trying to apply Band-Aids. “A partner should approach security in a holistic way,” he says. “If the discussion consists of a bunch of buzz words and tactical type approaches that are not guided by an overall strategic approach, it may not be an adequate partner.”

The bottom line? If you haven’t adopted an Internet security strategy, it’s way past time to get started.