Why is there such a gap in the thinking of American CEOs vs. the thinking of the American intelligence, security and military leadership when it comes to China?

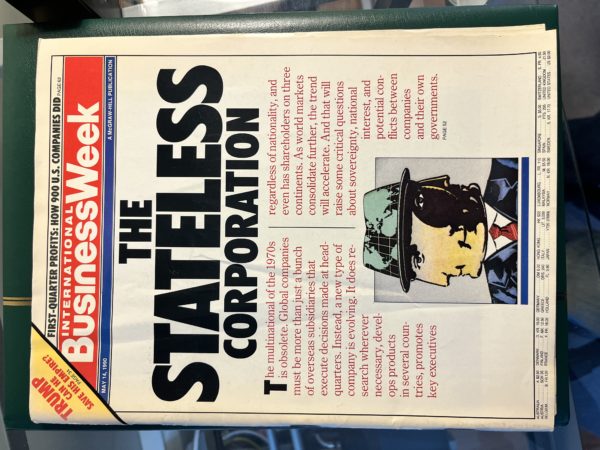

To help understand the gap in thinking, let me explain that in 1990 a team of us at Business Week wrote a cover story called The Stateless Corporation. We looked at the management and board compositions of major multinationals and examined their relationships with their governments. In the final analysis, we concluded that Japanese, French, Swiss and German CEOs recognized that they are part of the fabric of their nation-states. ONLY AMERICAN CEOs BELIEVED THEY WERE INDEPENDENT OF NATION-STATE CONSTRAINTS.

Another important element in American CEO thinking: Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago argued that a CEO’s only commitment was to increasing shareholder value and increasing profits every quarter. Although that argument has taken something of a beating in recent years, it still is a very strong theme in the thinking of many American CEOs.

This understanding worked because the U.S. dominated the global economy. Our security interests were not compromised by the actions of CEOs as they pursued their dreams of globalization. They concluded it did not matter where they invested, developed technology, manufactured or recruited talent, etc. Our national security was not affected by their stateless, globalized strategies. In fact, it may have helped us beat the Soviet Union.

Now comes China, which is suddenly the world’s second largest economy (far larger than the Soviet economy was). It is playing by a very different set of rules. It has learned how to co-opt these companies, to penetrate their IT systems, to steal or command their technology, to create such enormous profits for them, etc. CEOs continue to believe they can play both sides–that they have no commitment to U.S. national security.

So that’s where the rubber hits the road. We have to persuade American CEOs that they are part of America. Right now, we have CEOs and venture capitalists actively working in China to help the government (and the military) develop a full-fledged semiconductor industry as well as AI capabilities–at the same time that China is developing hypersonic missiles and building nuclear-capable launch siloes. At the same time it is sending its latest warplanes into Taiwan’s air space. This way lies madness.

These CEOs and their advocacy organizations are arguing that everything is just fine in U.S.-China relations if only we could get back to “normal.” The Chinese are consciously seeking to draw them in further and to use them as advocacy tools in the American policy debate. Look at how J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs have been granted permission to take over their local subsidiaries. Foreign investment in China is actually increasing.

As I argue in A Grand Strategy, I’m afraid it is going to take a showdown to move the conversation forward. The U.S. government is going to have to identify a particularly egregious set of actions and thrown down the national security hammer. If we make an example of one company, others could get the message that it is time to shift gears in their stateless China strategies.